Grand Rapids, Michigan, was home to artist Mathias J. Alten for nearly 50 years. His interest in continuing to live in West Michigan where his family had immigrated in 1889 has fascinated art historians examining his life and work. He planted his studio in Michigan’s second largest city, all the while pursuing his career within the traditional framework of European study and travel abroad. Traveling to paint in American art colonies was a habit Alten shared with his contemporaries, as was his participation in national competitions and exhibiting at well-known gallery venues. Scholars and authors have variously ascribed his preference for Grand Rapids as his residence to his desire for stability for his family, his adherence to an older style of painting that was still popular during his early years as an artist, and to his concerns regarding the rapidly shifting modern styles then in vogue in the nation’s artistic urban centers. Whatever Alten’s reasons regarding his choice, Grand Rapids remained his home and a frequent subject in his art. Within assessments of Alten’s oeuvre, a number of his paintings that draw upon West Michigan landscapes have received strong accolades, comparable to those based upon his more exotic European locales. His urban scenes, though fewer in number, also have a place within his catalog and reflect his close connection to the city and region he called home.1

This essay focuses on Alten’s Grand Rapids and the surrounding area’s connection to his work. Scholars of his art observe that his city was a center of furniture production, a bustling place, but do little to consider it beyond that level of context. Although certainly not a major center for fine visual art, the city was nonetheless a locus for dictating national taste in household goods and in the related visual marketing employed to sell it. Furniture makers in the city mass-produced household furniture, a reflection of the growing consumerism of middle-class America that challenged traditional cultural values of simple production and regional control over artistic taste. Designers worked to shape consumer preferences while also producing goods that would sell to national instead of regional markets. Simultaneously, during the time span of Alten’s career, Americans increasingly departed from farms to move to cities. This combination of manufacturing growth and urbanization, coupled with the artist’s attraction to the rural agrarian beauty found along Lake Michigan’s coast, the presence of wealthy patrons within the community, and his own unique outlook, all combined to shape Alten’s artistic career. Considering his life within the context of greater Grand Rapids offers a new vantage point from which to appreciate his artwork.

Grand Rapids already held a significant place in the business of producing household furniture by the time of Alten’s family’s arrival there in 1889. Building upon the city’s origins as a trading and lumbering center in West Michigan, cabinet makers and other entrepreneurs had utilized the natural resources of the region to establish a series of companies dedicated to furniture production and architectural trim for a regional market. Although the railroad had arrived by 1858, the production of the city’s craftsmen remained small in scale and on a regional level. In the years following the Civil War, however, these small firms began to reach beyond their immediate markets.

Handcrafted cabinetry and furniture was then, and still is, a mark of quality when combined with style and design. Cost, including such elements as hand-dovetailed joints, fine woods, and carved details placed many goods out of the financial means of most families. To break into a growing national market and challenge Eastern firms focused on producing handcrafted goods would require the use of machinery to drive costs down, not only for basic, low-cost furniture, but also for higher-end, more detailed pieces. Grand Rapids based furniture firms such as Berkey & Gay, Nelson, Matter and Co., and the Phoenix Furniture Company all entered into this new national market during the 1870s – some even maintaining sales rooms in New York City. Convincing buyers that machine-made goods were not of inferior quality came not only through pricing, but also through the appearance of their products. These challenges also stemmed from cultural changes in the United States as the nation became increasingly industrialized and production became tied to technological advances. Additionally, westward expansion and the growth of the middle-class fueled a new demand for home furnishings. For example, new travelers along the nation’s expanding railway network required hotels with beds and furnishings, all of which offered a middle-range market outside of low-cost items or handcrafted luxury goods.2

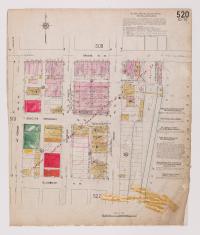

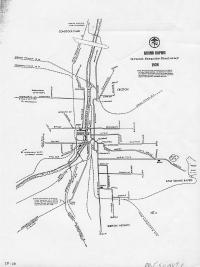

To achieve this change in scale and scope of production, furniture companies required more workers, larger factories, and a source of power for their new machinery. Settlers from the Netherlands and Poland comprised a large number of workers within the early factories, but during the 1870s and 1880s immigrants coming from Germany, Lithuania, Sweden, Italy, and other parts of Europe supplanted them. When Alten’s family moved to the West Side of Grand Rapids in 1889, they joined a vibrant community along both sides of the Grand River. Breweries, stores, churches, and cultural institutions all gave minority families a sense of place outside of the dominant, more established community. Within a compact walking city, Bridge Street served as a major business district that tied all of these communities together. A casual reading of the Schwind and Alten Company ledger reveals that even with a strong German client base, Irish, Polish, and Dutch families also purchased paint and wallpaper from his father-in‑law’s store, that Alten helped to operate with his wife, Bertha. Although the great mansions along the bluffs of the eastern valley reflected a clear hierarchy, the short distances between ethnic group neighborhoods on Grand Rapids’ West Side meant that Alten would come into regular contact with the growing community’s working- and middle-class families and the factories that employed them (Fig. 1).3

The influence of the furniture industry would touch the budding artist directly. While he helped to operate the family business, Alten would also find work as a furniture decorator in the factories that lined the streets and river. Companies such as Phoenix utilized decorators to apply carved or painted details to their high-end items, to combat the perception that machine-made furniture was a lesser product than handcrafted pieces. Alten’s artistic skills and prior experiences as a decorator made this type of work a natural fit for him. Despite their growth, the furniture companies remained relatively small places, with the largest having hundreds, not thousands of workers. Those at the top of the worker hierarchy gained recognition, and accordingly, Alten’s work at Phoenix in 1896 brought him into contact with designer David Wolcott Kendall who would become one of his early supporters.4

By the time Alten started his career as an artist in earnest during the 1890s, the furniture industry had shaped not only the employment and demographics of the community, but the geography of the city as well. The Grand River, a familiar subject, was typically depicted by him as a rural idyll as it flowed on through Kent and Ottawa counties to Lake Michigan. Within the confines of Grand Rapids, however, the river showed both the beauty of nature as well as the alterations imposed by industry. In Alten’s 1904 painting The Grand River (Fig. 2), the viewer looks to the southwest above the Sixth Street Bridge at sunset. Although the foreground depicts trees and the varied hues of dusk, a closer examination reveals the steam from boats, a water tower, and a backdrop of factories clustered along the riverbank. This is an industrial landscape, one that produced furniture of great variety and beauty, but at the expense of defacing and despoiling the river (Fig. 3).

The rapids of the Grand River presented a block to navigation, requiring a canal and locks to be dug along its eastern shore. With a 16-foot drop in elevation from Comstock Park, the rapids also offered water power to furniture factories. Harnessing that energy required the construction of a power canal along the western bank to control the flow to water wheels and by the 1880s, one of the earliest hydroelectric generators. Even after the introduction of coal-fired steam boilers for powering factory machinery, the canal remained an important power and cooling source for factories ever mindful of keeping costs down. A network of foot and vehicular bridges, retaining walls, and trees helped to maintain the structural integrity of the waterway. Alten’s 1914 painting Westside Canal in Winter (Fig. 4) looks north along that power canal, most likely just above its southern exit north of the Grand Rapids and Indiana Railroad Bridge (known today as the “Blue Bridge”). The bare trees offer a view of nature, while the Voigt Crescent Flour Mill on the right side, hidden by trees, and then the Hot Blast Feather Company, and others on the left side of the painting, flank the canal. The winter scene shows the flow of the canal and the steam rising from the water intake and outflow from the factories. It is a scene that stands in stark contrast to Alten’s sunnier European images 5 (Figures 5, 6, 7, and 8).

Similar to the earlier view of the Grand River, Looking North Along the Grand from Lower Island (Fig. 9), was painted in 1909 from the vantage point of one of the small islands south of downtown and just above Wealthy Street. Alten would likely have been standing on the island just north of the Grand Rapids Pere Marquette Swing Railroad Bridge. Behind the trees in the foreground can be seen the shapes of factories lining the river. A figure by the island stands in a boat, reminding the viewer of the river’s role as a transportation, recreation, and food source well into the twentieth-century. Hidden from view are the more obvious signs of bridges, railroads, and other highly intrusive technologies. The huge bulk of the Voigt Milling Company’s structure seated between the Westside Power Canal and the river also helps to situate the scene. The Grand River, though viewed with the island in the foreground, remains a working river, one shaped and defined by industry, regardless of artistic license.

The 1905 painting View of Gas Works from Lower Island on the Grand is composed from a similar but reversed vantage point (Fig. 10). Looking southeast from either the same small island or one closer to the river’s eastern shore, the viewer’s eye is connected to land where the city’s garbage incinerator, public market, and baseball field once stood. The 1884 city gas works at the southeast corner of Market and Wealthy streets looms in the background. The 50-foot-tall gasometers — holding tanks and pressure regulation devices for coal gas used for lighting and heat — dominate the skyline. Located at the base of the Grandville Avenue ridge, these towers could be seen across the area and remind viewers that, even with the inclusion of a horse-drawn wagon in the composition, the growing influence of modern technology marked the city’s geography (Figures 11, 12, and 13).

In this painting, completed shortly after the great flood of 1904, Alten records a riverfront that would soon be heavily reworked. Responding to the devastation, the city would embark on flood-control efforts and constrain the river’s course even further with concrete walls and dredging.6 Indeed, the Alten family’s decision to move to a newly built house in 1906, away from the West Side, indicates not only a change in status, but also a move away from the periodic flooding experienced there. Alten’s view of the river obscures the bridges, garbage carts, and factories, pushing them into the background of an idealized view of the waterfront. Among his most appealing urban images is Valley City, Late September (1913) that looks out across the city (Fig. 14). Unlike the images set closer to the river, the wider view reflects nature in the foreground with the urban landscape at a remove.

These artistic depictions of Grand Rapids’ waterfront show the maturity of the city’s furniture industry, achieved by the early part of the twentieth century. After garnering acclaim for their machine-made goods at the 1876 U.S.

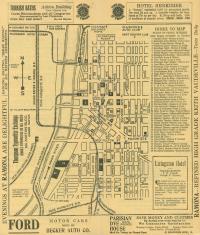

Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, and at other major fairs and exhibitions, Grand Rapids manufacturers escalated their attempts to carve out a greater share of the national market. Local manufacturers consolidated their efforts to fend off competitors from Chicago and New York. Beginning in the late 1870s, manufacturers jointly sponsored the Furniture Market, a twice-yearly event held in January and June. This drew hundreds of buyers to the city, along with producers from cities across the nation, and cemented the significance of Grand Rapids to furniture production and marketing. The month-long event fueled not only the industry, but also supporting businesses and community institutions. Artists such as Alten, with his studio at various downtown locations, obtained business and interest from the buyers, families, and other tradesmen coming to the city. Many of his painting exhibitions coincided with the Furniture Market. This brought him further into contact with furniture designers and salesmen who now no longer conceived of manufacturer’s sales floors comprised of rows of product, but rather as accessorized sample rooms furnished with entire matching suites (Fig. 15).7

Furniture design during the early 1900s moved away from Victorian styles to a more holistic approach based on the aesthetic concepts of the Arts and Crafts Movement. Companies such as Stickley Brothers hired talented artists and designers from around the world to detail and create furniture with a cohesive design aesthetic based on basic forms and natural materials. David Robertson Smith, Charles Limbert, David Wolcott Kendall, and their colleagues designed furniture that, while heavily machinemade, no longer so clearly reflected that fact. Although beautiful to the eye and drawing on a greater variety of woods, styles, and colors than ever before, the taint of being mass produced would certainly remain a difficult perception to overcome. Although not the kind of visual art created by Alten, the applied artwork of Grand Rapids’ furniture industry was not without its own design merit and artistic creativity.

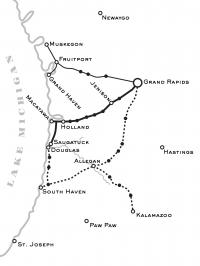

Much of Alten’s artwork, reflects a preautomotive world both in city and country. Picnic at Macatawa, painted in 1904, is often discussed as an Alten family scene, one that draws on the then-popular motif of a family gathering, and also in its use of color and alternating sunlight and shade (Fig. 16). The locale of the painting is interesting on its own. The trees and the steep sandy slope in the background indicate that the family is picnicking on the back slope of the sand dunes along Lake Michigan. Beech and maple trees, varieties of conifers, ground cover, and beach grass serve as anchors to hold the massive dunes in place against the winds coming off the lake. Compared to the vast open expanse of sand and sunshine of the lake side of the dunes, the back dunes offered cool, sheltered oases where families could enjoy both the big lake and, in some areas, secondary bodies of water like Lake Macatawa. People could travel there either by railroad or via the electric interurban. Holland, Michigan, the site of Lake Macatawa, was linked to Grand Rapids via the interurban in 1901 with the opening of the Grand Rapids, Holland, and Lake Michigan Railway. Interurbans were clean, powered by electricity, not by sooty, coal-fired engines. They were exclusively for passengers, not freight, and were priced competitively with traditional rail lines. Streetcars brought passengers to the Interurban Station, next to the Pantlind Hotel downtown (today’s Amway Grand Plaza Hotel) where they could then take the advertised 30-minute interurban service to Macatawa Park. If they were interested in sailing across Lake Michigan, the end of the line was at the Graham and Morton Transportation Company’s Holland dock and the steamship, City of Grand Rapids, which made an overnight run to Chicago8 (Fig. 17).

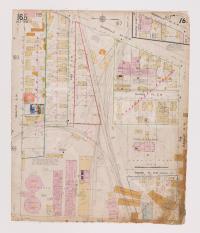

Family stories recount how Alten was often losing his gloves on streetcars, even forgetting where he parked his car while on artistic rambles, having to return home via streetcar.9 Beyond anecdote, they reveal that the artist could easily travel around the region both with and without an automobile. It is useful to note that Alten consistently resided along the city’s major streetcar routes: on the West Side near Bridge Street; later, at the house built in 1906 on Hope Street at Fuller Avenue, near the Lake Drive line and finally, in 1913, at the very end of the Fulton route, at 1593 Fulton Street, with its turnaround at Ball (present-day Alten) Avenue. Two of the streetcar routes, Lake Drive and North Park Line, took urban riders to Ramona Park on Reeds Lake or to North Park with its West Michigan State Fairgrounds. Sailboats on Reeds Lake painted in 1930, is a scene that can be viewed even in the present day (Fig. 18). Recreation, much as depicted in the Picnic at Macatawa painting, generally took place at venues made accessible by public transportation. While the automobile was, by the 1920s, a widely adopted mode of transportation, roads, maps, and directional signage were still evolving for ease of use. The earlier painting A Bayou at North Park (1898) depicts the Grand River along its northern path through the city, upstream and away from the major factories and the runoff from their facilities (see page 46). Streetcars traveled to these recreational locations as a way to gain revenue on weekends when overall traffic was far lighter and people desired to get outside of their neighborhoods. Even for his paintings that depicted the Grand River’s industrial heart, Alten could easily make his way to and from his locations using the streetcar and interurban network10 (Figures 19, 20, and 21).

The rural landscape of West Michigan was a regular and well-regarded subject of Alten’s plein-air painting. Despite a preference for depicting the simplicity of traditional farming, his ability to reach these agrarian areas undoubtedly came by way of technological innovation. Driving a horse and buggy is similar to driving a car in that much attention must be paid to the horse, the road, situations that may alarm the team, and the weather. The electric interurban allowed for a more passive journey, traveling through the countryside while paying attention to what was going on along the right-of-way, sometimes along major roads, and at other points along its roadbed and tracks. The 1903 opening of the Grand Rapids, Grand Haven, and Muskegon Railway opened a second electrified route from downtown Grand Rapids to the Lake Michigan shore, ending at Muskegon instead of Holland. The multitude of stops on a local route allowed passengers to exit the interurban at locations such as Berlin (Marne), Nunica, or Mona Lake and then to explore either on foot or bicycle.11

Such access afforded Alten great amounts of freedom and choices of landscape subjects, as indicated by the breadth and range of his regional artworks. While his family recalls his working while accompanying them on excursions, he also traveled a great deal on his own. Particularly in the years before the automobile, travel was a logistical exercise and the coming of an affordable and far-reaching transportation network was viewed as a tremendous breakthrough. Farmers with Horse Cart (1914) and Plowing at Sunset (1908) illustrate not only a common theme of work horses and the agrarian countryside surrounding Grand Rapids, but also the range of picturesque locations available to the artist (Figures 22 and 23). These paintings, and others such as Gathering Pumpkins at Sunset (1907), further reflect Alten’s interest in capturing traditional farming scenes at harvest time. Throughout West Michigan, autumn harvests still relied on horse and manpower to bring in crops on small farms. Today’s mechanized farms with highly specialized crops and equipment could not have been imagined, but the widespread use of farm machinery would start to emerge during Alten’s lifetime, even though he chose to ignore it as an artistic subject (Fig. 24). Working with his remarkable speed and detail, Alten’s ability to travel distances at different times of day also made living in Grand Rapids a benefit. While he could and did spend time at various American art colonies, the range of local subjects, along with his own enjoyment in looking about to find subjects to paint, offered ample options upon which to spend his time.

Alten’s rural landscapes create a sense of connection for viewers to a natural landscape that is both familiar and distinctive. Landscape with Figures and Sheep (1900) shows a composition and subjects similar to his urban works of the same period (Fig. 25). Much as in his earlier work, The Grand River (1904) (Fig. 2), Alten situates his composition on a road along a bluff near the river’s bank, similar to what one can find today along Leonard Street in Ottawa County. The sloughs and bayous along the Grand River drew the artist’s attention time and again. When combined with the reoccurring theme of rural agriculture, it is an evocative image connecting him to West Michigan.

Kent and Ottawa counties had undergone a dramatic change — much as the Grand River had — because of intensive logging, farming, industrialization, and urbanization. Both counties had become primarily agricultural areas of great diversity. No longer thickly forested with a combination of pine and hardwoods, the rolling hills of Kent County blossomed with orchards and fields of corn. Ottawa County, with its muck farms and lakeshore orchards, shared its neighbor’s productivity. Despite this seeming bounty, Alten’s 1916 work Late Summer Fields, Michigan reveals a hidden fragility to farmland that was present in Ottawa County and along the lakeshore (Fig. 26). Having been originally forested, much of the farmland along the lakeshore had a sandy base that strong winds would reveal as “blowouts” that required care and attention. The limited topsoil layer would eventually be worn out by continual agricultural practices and, when faced with drought and wind during the 1930s, would collapse that county’s farm economy. Alten’s art captures not only the beauty of West Michigan but also the transitional period from the small farms of the nineteenth century to the modern mechanized entities of the twentieth

Alten’s Grand Rapids would experience its high point during his lifetime as the nation’s “Furniture City.” The combination of the semi-annual Furniture Markets, innovative design, and aggressive business methods made it the center of the furniture industry and Michigan’s second largest city. By the end of his life in 1938, however, the years of its success began to wane. The Great Depression completed the erosion of the city’s pre‑eminence in household furnishings, and the Grand River reflected the hard use industry had placed upon it. The surrounding rural areas would draw together, consider their circumstances, and find new ways to continue farming and building. While not gone, the vestiges of what the artist witnessed and recorded remain only if one looks closely enough.

he city Mathias J. Alten called home during his lifetime did not lack for self-confidence in its own place or identity. The German-born artist took unpopular views during World War I when compared to most Americans, but nevertheless his friends and patrons ensured his continued work within their community.12 The city’s furniture manufacturers and those in related supply firms and banking remained a closely tied group, shaping their firms to retain their premier position and prevent outsiders from undermining their hard-won success. To that end, the city created a self-contained community, confident and secure in its ability to support an artist like Alten who, while not distinctly wealthy, could find ample opportunity for creative expression outside of the traditional centers of art in the United States.

William H. Gerdts, “Mathias J. Alten: Journey of an American Painter,” in Celeste M. Adams, editor, Mathias J. Alten: Journey of an American Painter (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Grand Rapids Art Museum, 1998), 20-21; Mathias Alten, “I Have a Beautiful Country to Work From,” in Steve Ostrander, editor, The Sweetness of Freedom: Stories of Immigrants (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2010), 29-49; Additionally, the dates and locations are taken from James A. Straub, “Chronology: The Life and Work of Mathias J. Alten, 1871-1938,” in Celeste M. Adams, editor, Mathias J. Alten: Journey of an American Painter (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Grand Rapids Art Museum, 1998), 111-143; and James A. Straub, Mathias J. Alten (1871-1938): A Catalogue Raisonné, accessed, September 20, 2015, http://www.mathiasalten.com

James Stanford Bradshaw, “Grand Rapids Furniture Beginnings,” Michigan History 52 (No.4, 1968), 279-298; James Stanford Bradshaw, “Grand Rapids, 1870-1880: Furniture City Emerges,” Michigan History 55 (No.4, 1972): 321-341; Christian G. Carron, Grand Rapids Furniture: The Story of America’s Furniture City (Traverse City, Mich.: Public Museum of Grand Rapids/Village Press, Inc., 1998), 38-43.

Schwind & Alten Co. Ledger, Box 7, Mathias J. Alten papers (RHC-28). Special Collections and University Archives, Grand Valley State University Libraries; Edward G. Gillis, Growing Up in Old Lithuanian Town (Grand Rapids: Grand Rapids Historical Commission, 2001), 45-52; Anthony R. Travis, “Mayor George Ellis: Grand Rapids Political Boss and Progressive Reformer,” Michigan History 58 (No. 2, 1974): 101-130.

Camelia Alten Demmon, “Memories of Father: Mathias J. Alten, 1871-1938,” Box 1, Mathias J. Alten papers (RHC-28). Special Collections and University Archives, Grand Valley State University Libraries. Carron, Grand Rapids Furniture, 62-69.

Z.Z. Lydens, editor, The Story of Grand Rapids: A Narrative of Grand Rapids, Michigan (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Kregel Publications, 1966), 191-192.

Lydens, The Story of Grand Rapids, 118-119.

Carron, Grand Rapids Furniture, 71-78.

Carl Bajema, Dave Kindem, and Jim Budzynski, The Lake Line: The Grand Rapids, Grand Haven, and Muskegon Railway (Chicago: Central Electric Railfans Association, 2011), 13, 80; Donald L. van Reken, The Interurban Era in Holland, Michigan (Holland, Mich.: self-published, 1981), 67-92; Robert Kline, “Grand Rapids — Holland Interurban Line,” accessed November 5, 2015, http://godwin.bobanna.com/interurban_gr_holland.html.

Gloria A. Gregory, “My Grandfather and Me: Sketches of Alten,” public presentation Muskegon Museum of Art, April 6, 2011, box 1, folder “Biographical File,” Mathias J. Alten Papers, RHC-28, University Archives, Grand Valley State University Libraries.

Michael Knopf, “Don’t Worry, Relax!: Public Policy, Franchises, and the End of Street Railways in Grand Rapids, Michigan, 1926-1935,” Grand River Valley History 24 (2009): 5-18.

Bajema, The Lake Line, 13.

Gloria Gregory, “Mathias Alten, The Man (2001),” Box 1, Mathias J. Alten papers (RHC-28). Special Collections and University Archives, Grand Valley State University Libraries.